23 September 2021

Why most Wholefood ingredients and most other food products will rise in price throughout 2022.

Ever since Australia started deregulating in 1983 under Paul Keating, we have operated under the assumption that Australia would require no special national investment programs to ensure our trade goods are internationally competitive, supply of essential goods will be maintained locally, and that competition and monetary policy alone could be used to control both price and wage inflation.

Recent events are highlighting that this may no longer be true (and hasn't been true for a while). We can only speak with authority about our small corner of the overall supply chain. Ingredients sourced directly from agricultural supply-chain both here and overseas. Over the last few years (and accelerated over the last year) we have seen fundamental changes that no one in living memory overseas or locally has seen before.

For now, much of this has been hidden from Australian consumers and impacts on our terms of trade, but that will not likely last as cheap stocks are used up, demand increases and a temporary glut of fresh product that usually sells to food services start to disappear as we re-open in late 2021.

Just a few issues we are dealing with as we head into 2022:

Cost to ship a 20ft and 40ft containers have increased by on average 333% in just a single year. A fact that hits agriculture hard given low value of products.

Availability of shipping capacity for both import and export is declining as containers are prioritised onto the most profitable routes.

Simultaneous extreme weather, both heat and rainfall events are impacting multiple growing regions at the same time with limited carry-in 'buffer' inventory.

A war for prime agriculture land is erupting as investment scheme speculation or government subsidies (and mispricing of water/land use) drive substitution of nutritious crops with cotton, sugar, soya and canola.

Here are just a few of the impacts:

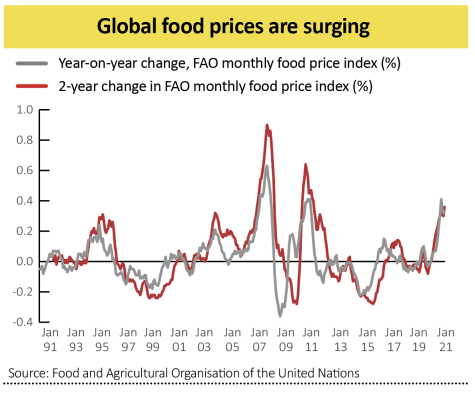

An average trend downwards in agriculture prices over the last four years is now suddenly and violently reversed.

Importer's inability to lock-in future container freight rates and rationing of product availability to purchase will slowly erase any price discounting.

Whilst this creates some potential challenges for our business, it is a bigger strategic problem for the country.

Can we solve the ocean freight issue?

What if over the next year Australia:

Cannot secure enough container tonnage to support its export industries and ensure continues supply of imported products on which we depend?

Sees price inflation jolt upwards affecting key demographics that cannot offset those costs with lower interest rates on their mortgage, working more hours or buying cheaper electronics?

History tells us that once upon a time trading nation's felt that ownership of their own merchant fleet was essential to their national prosperity if like us, they depended on international movement of goods.

Over the 19th and 20th century European economic leadership moved from Italy and Spain to the Netherlands and then onto the UK. At one-point 1914, UK accounted for 47.5% of the worlds modern steam vessel tonnage.

By this century, control of shipping was moving towards Asia. Looking beyond flags of convenience, ownership is increasingly concentrated within China, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. The UK's market share of shipping tonnage has fallen by over 95% over eight decades to 2010.

Today fast fashion, built-in obsolescence of electronic devices and reduction in overall lifespan of goods means that there is significantly more shipping capacity tied up in supplying countries around the world.

This growing transport capacity constraint is not new. In part, solving a problem they have contributed to, the smart folks at Amazon realised this and started building their own shipping fleet a while back.

What could we do here in Australia:

Create a national subsidy for export containers to ensure that we can support freight rates necessary to export our products. We do it for oil/gas at least.

Commission a merchant marine of container ships (we can't just leave it to the Greeks). We could buy a lot of ocean freight capacity for the price of 8 submarines.

Apply additional tariffs to products creating externalities and tying up shipping capacity – i.e. fast fashion, items that can't be recycled, cheap toys

Can we solve the agricultural product issue?

There are a lot of people working on weather modelling and climate change mitigation strategies. The reality is that it likely to continue getting significantly worse and we are just arguing now about how much worse.

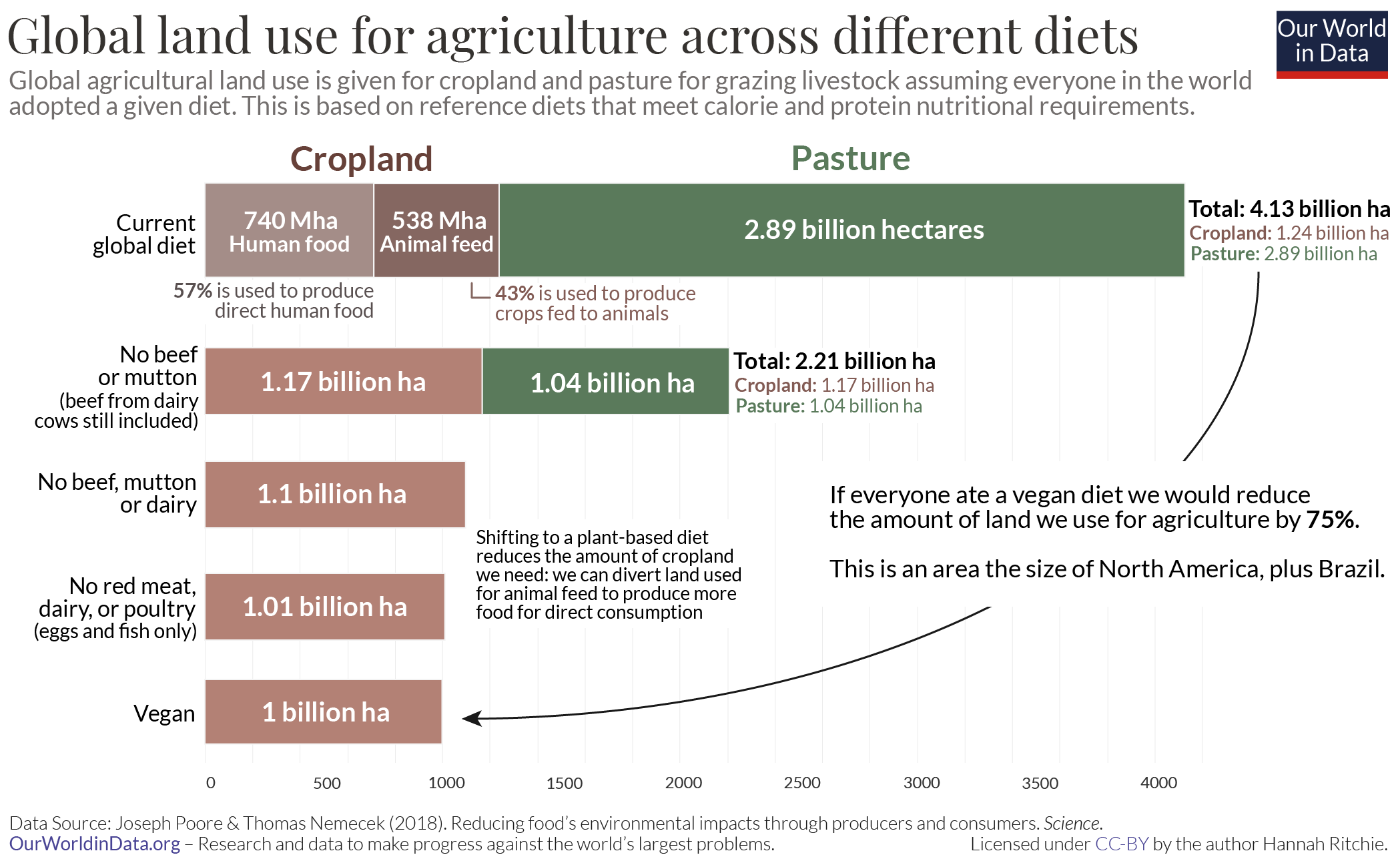

A lot of that prime agricultural land is now being taken up by crops that are primarily used to feed livestock and cattle.

Whilst the below data is not specific to Australia, it gives an idea of just how much of growing challenge we have in managing scarce productive land.

This chart doesn't give the full story because there are crops like cotton (which isn't eaten), tomatoes (which have a significant food wastage component) and oilseeds (particularly for use in refined manufactured foods) that are taking a larger and larger share vs. traditional agricultural crops that have formed the bedrock of lots of the global populations diet.

So, what can we do here in Australia:

Specifically outlaw or restrict agricultural investment schemes that distort demand signals and lead to overinvestment in land (and drive prices up.)

Look to restrict further encroachment of development on prime agricultural land, of which Australia does not have much to start with.

Encourage more diverse diets, reducing overall meat consumption (not veganism) and exploring the reality that like coal, we might not have our beef export market for ever.

Keep doing what a vibrant agtech sector is already doing and exploring ways to dramatically improve grower productivity and soil quality.