25 July 2023

Where are all the Laird (Green) Lentils?

You might have noticed that dried Laird Lentils (often called brown lentils) and French lentils (also called green lentils) are missing from the shelves. Or not. However, there are plenty of Australians who have and many frustrated customers who are feeling the lack of product in the channel.

There are many detailed articles and reports by scientists, agronomists, and government policy specialists available publicly, but this article is targeted at our customers and those interested in the intersection of economics, supply chain, innovation, risk management and agriculture.

This article will cover:

Where laird lentils and French lentils come from.

Why these lentils are only sporadically available this year.

What potential policy changes and solutions exist.

Role of innovative technology and processes.

Where do our Green Lentils come from?

Main growing regions for lentils

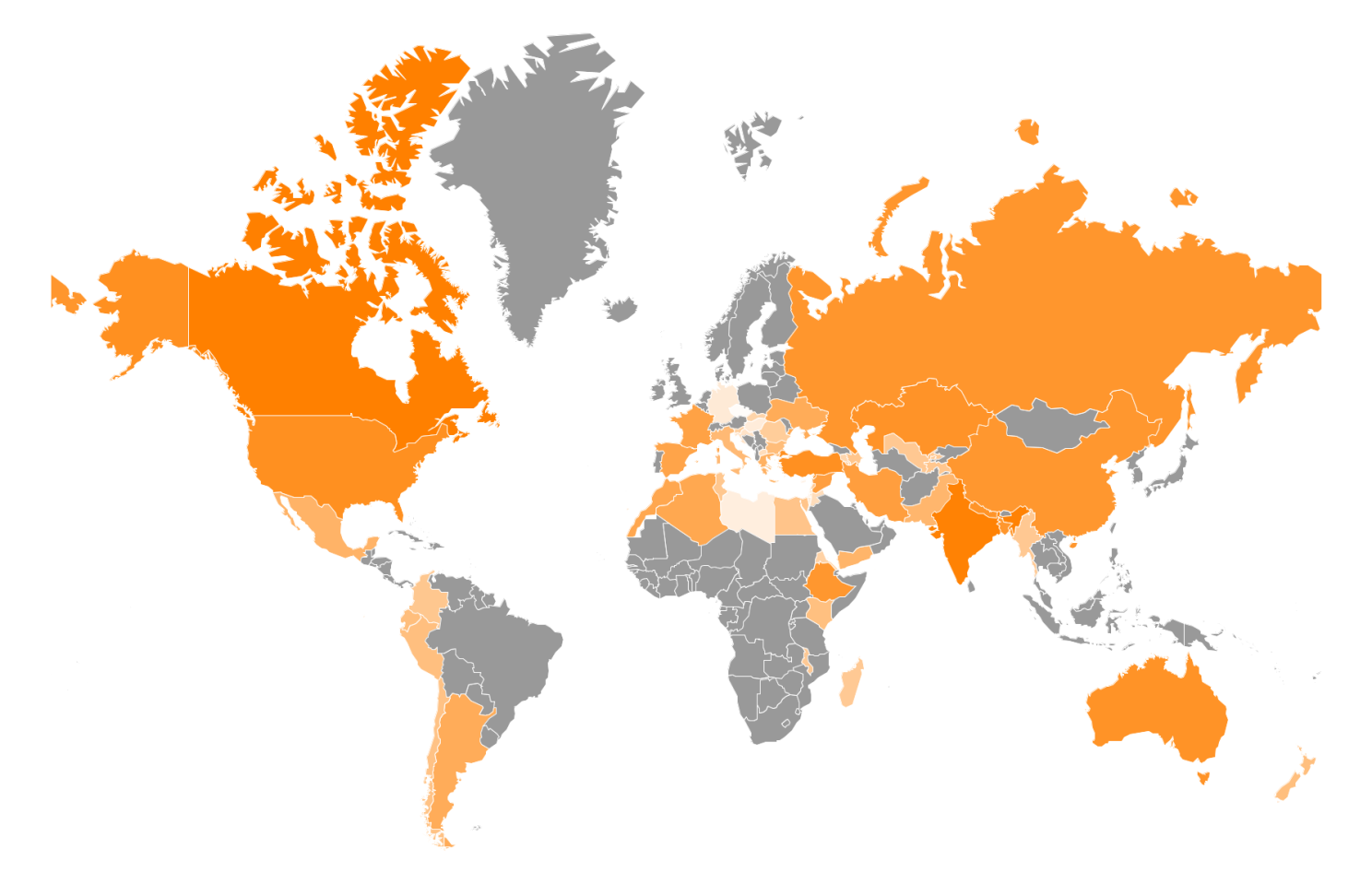

Canada is our biggest supplier of both Laird Lentils and French Lentils. There are multiple importers who bring in regular containers – we are one of them.

They are also locally grown in small quantities primarily for the domestic market – but here in Australia are considered a niche crop unlike Canada which suppliers multiple major export markets.

Theoretically Europe also grows French, Spanish and Green Lentils – but due to droughts and other conflicts they have not had even enough product to cover domestic demand.

Most buyers in the market would agree that Canadian Laird Lentils (Green Giants) are usually larger in size and greener in colour due – this is due to a combination of soil and weather conditions.

Why is the supply interrupted?

Canadian processors and exporters of lentil seeds to Australia must jump through painful hurdles to export the seed to Australia. Their other major export markets do not have the same hurdles and have significantly higher demand.

These hurdles include the seed being tested only after processing, bagging, and labelling of a specific export lot. They are expensive, time consuming and carry a risk of failure regardless of the best efforts of a processor to screen their grower intake for disease.

In recent years there have been more random failures of seed lots during testing has meant that some exporters have ceased supplying Australia at all. Other processors supplying our market are not able to export planned shipments meaning long, unexpected gaps in supply to our market.

Australia imposes strict quarantine measures on the import of lentils from North America due a perceived risk that imported seed will potentially spread into Australia the disease Lentil Anthracnose which has not been spotted here in the wild but is prevalent in Canada.

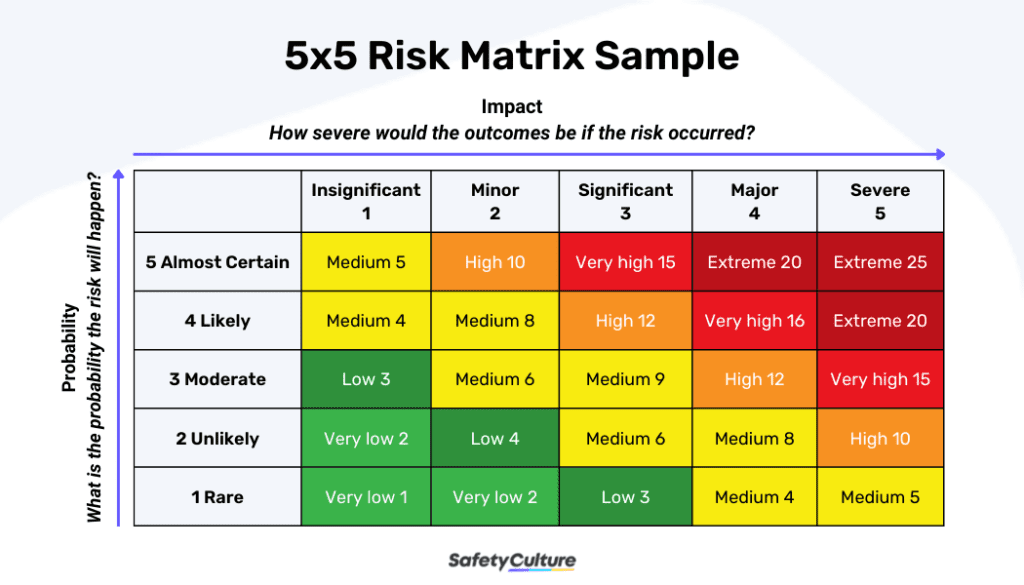

Even though the risk would be at a minimum unlikely but should be rare – the severe impact on our agriculture has fairly led Australian Biosecurity to label the introduction as a medium risk.

Severe impact if the disease spreading

Lesions caused by the disease

This disease is caused by a fungus called Collectrichum truncatum which has evolved to the ability to attack lentil plants – unlike many related varieties of the pathogen which exist in Australia but do not attack Lentil plants.

The spread of this disease is quantified as a substantial risk as it would significantly impact a major agricultural commodity.

Unlike Laird and French Lentils, Australia is a major exporter of Red Lentils all around the world. In 2022, we had a forecasted production of 924,000 metric tonnes across all varieties of Lentils. At an average farm dressed price of AUD800/MT – AUD1200/MT that is 700M+ at least in economic output.

In Canada, it has been reported that yield losses may be as high as 60-70% if the disease gets established and is left untreated. In Canada, they use a combination of fungicide and seed testing to avoid the further spread of disease and to treat the disease if identified in a particular field.

In Australia, it is viewed that our longer growing season would mean multiple applications of fungicide being required that would potentially make our export pricing uncompetitive – even if it works to control spread.

Rare likelihood, but it is theoretically possible

Collectrichum truncatum is a tough bastard of a fungus. Its spores can survive in soil for up to four years and it is possible for the spores to contaminate and live on the seeds themselves. Although no spread has ever been proven through the sale of lentil seeds – the theoretical risk of these seeds being delivered into a growing region and used for planting or exposed to the environment exists.

Yes, product imported for human consumption via retail outlets in small packages and sold to manufacturers would not yield this risk – but it is not possible for biosecurity to control where and how the seed is used and without that control they cannot trust that the disease could not be spread by imported seed.

Why isn't there Australian product widely available

In Australia, our growers (farmers) will fairly focus on planting the crops that give them the highest profit margin for the lowest risk of crop failure or unexpected yield loss due to quality issues.

One way to balance that risk is to grow crops that will have markets, even when quality is an issue or where we know that Australia can compete on price due to competitive freight routes. That means we grow varieties more likely to be consumed in the Middle East and Asia – vs the Americas and Europe.

With the significant rain events that occurred late in the harvest cycle in 2022, our already small crop was significantly weather impacted with disease, skin wrinkle and mould issues. This has meant a lot of the Green Giant (what we call Laird Lentils in Australia) is not suitable for sale to the packaging market for retail.

What are the potential solutions

Put in place new control measures and a better trust framework

Ideally all importers and Canadian processor/exporters would love Australian Biosecurity to ease the extremely costly and high-risk measures imposed to control the potential for spread of this disease into Australia. This seems unlikely given the thorough scientific written by Kurt Lindbeck and Rebecca Ford at University of Melbourne. The full policy and justification can be found at National Plant Biosecurity Diagnostic Network.

However, this policy does rest on the shaky theoretically possibility of seeds imported being moved and used in significant quantities to an at-risk growing region and we could look at alternative testing and control procedures.

Australia could, however, work with Canada to provide a more pragmatic testing regime that authorised certain trusted processors to not wait until a production lot for a specific container consignment has been bagged and labelled and instead puts in place a mix of traceability to grower field and testing on intake to reduce the already extremely low likelihood of the disease spreading.

We could also impose legal implications for using imported product in anything other than consumer packaging sold through retail for importers and distributors further reducing the risk. Today, we can put in place strict traceability of product lots all the way to individual packages of 500g product. We should explore ways to leverage that technology in a regulatory framework that further minimises risk – going as far as to enforce special labelling.

Subsidise local growers to ensure better food security

The reason we depend on Canadian imports for most of our supply is that our own local growers fairly make the decision that there are alternative crops that they should invest their scarce resources in growing.

Left to the market and based on price and quality – many of Australia's consumers will choose a Canadian origin lentil – even if the price is significantly higher. Of course, if no option existed, they would buy Australian – if it were available.

Our growers know this but can't know in advance when making planting decisions if the Canadian crop will be available or not – so why risk planting.

Australia could make the decision that a certain tonnage of product is always subsidised to remove the risk from growers – including covering costs of insurance related to higher growing risk. This would mean at a minimum Australia would have supply of a domestic tonnage.

Such subsidies may fall afoul of our existing trade agreements (I don't have time for that examination) – but the world in changing in relation to nation state ensuring improved supply chain security anyway.

Role of Innovation

Disease management and control includes:

Genetic testing and screening technologies for disease/fungal spores

Seed genetic breeding programs to evolve varieties resistance to disease

Real-time on farm monitoring of plant health – including AI and drones

Supply chain traceability and package labelling innovations

The following were the major sources of information used:

Industry Biosecurity Plan for the Grains Industry – Threat Specific Contingency Plan for Lentil Anthracnose,Dr Trevor Bretag, 2008.

National Diagnostic Protocol (NDP) for Colletotrichum Lentis, SPHD Agriculture.gov.au, 2021